Mutualism3

Mutualism is an interspecific interaction where both species benefit from the interaction. Each mutualistic partner “helps” the other only for the benefits that it gains. There must be a high benefit to cost ratio in order for this relationship to be successful long term.

Pollination1

90% of flowering plants are insect pollinated. Plants gain reproductive benefits and insects usually either gain food or reproductive benefits.

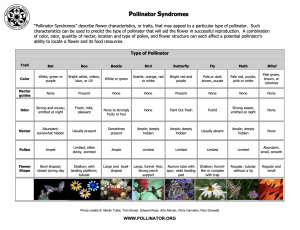

Pollinator-mediated floral trait evolution leads to ‘pollination syndromes.’ Pollination syndromes are a type of coevolution and can be a helpful tool for predicting how plants are pollinated. Typically, inflorescence structure is influenced by pollinators and pollinators are drawn to specific floral colors, shapes, nectar, and pollen.

Darwin’s Orchid and the Sphinx Moth

- *****Green means good for the organism (either Moth or Orchid) natural selection will act in favor of this

- *****Red means bad for the organism (either Moth or Orchid) natural selection will NOT act in favor of this

- An extraordinary example of coevolution. Coevolution is the evolution of two interacting species, each in response to selective pressure imposed by the other species.3

- The Madagascan hawkmoth was predicted to exist by Darwin and Wallace in 1862.7

- In order for the moth to pollinate the orchid, the moth head needs to make contact with the reproductive structures of the orchid. This favors a longer nectar tube so that the moth has to be touching the flower in order to get the nectar reward.2

- In order for the moth to get the nectar reward, it needs a long enough proboscis, or tongue, to reach the bottom of the nectar tube without touching the reproductive structures of the orchid. Therefore, a longer tongue is selected for.2

- Charles Darwin was sent an orchid specimen from Madagascar and noticed it had a remarkable nectar tube that measured 30 cm.7

- Darwin predicted that there must be a pollinator with a tongue long enough to reach the nectar.7

- Alfred Russel Wallace and Darwin predicted that it would most likely be a hawkmoth due to the fact that a hawkmoth with a long proboscis was found on the African continent.7

- The sphinx moth is endemic to Madagascar and is a marvel of coevolution.2

- This is an example of the Red Queens hypothesis ‘it takes all the running you can do to stay in the same place.’ The moth evolved a longer tongue in response to the orchid evolving a longer nectar tube and so on and so on until the two evolved such unique anatomy that they become obligate pollinators.2

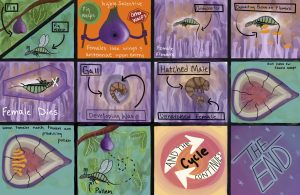

Fig and Fig Wasps4

- This relationship is over 90 million years old

- Fun fact: figs are inverted flowers. This means that their pollination is a very tricky business that can only be completed by a very specific pollinator.

- In this case, the very specific pollinator is the fig wasp and both the fig and fig wasp are completely dependent on each other for survival, making this an obligate mutualism relationship—both would die without the other.

- Pregnant female wasps carrying pollen from fig they emerged from find a new fig to enter. The hole at bottom of fig is highly selective and only lets in specific species of wasp. Females typically lose wings and antennae

- Once inside, the wasp lays fertilized eggs inside the flowers of the fig.

- While the wasp is depositing eggs (ovidepositing) she pollinates the flowers with the pollen she was carrying from the fig she emerged from.

- Those flowers, once pollinated, start growing seeds in the ovary

- Once the female deposits her eggs and fertilizes the flowers, she dies

- The plant creates a gall that protects the developing wasps

- Male wasps emerge first, and once emerged, they impregnate the unhatched female wasps and bore holes out of the sides of the fig so females can escape.

- When the females emerge, the fig has just started to produce pollen and the females carry this pollen with them out of the fig and the cycle starts again

Yucca and Yucca Moth

- The relationship is over 40 million years old.6

- This relationship is built on the foundation that, since the 1870’s, no other species have been known to pollinate yucca flowers except the yucca moth. Yucca and moth larvae do not feed on anything other than yucca seeds. This kind of relationship is known as obligate mutualism as both species would die without the other.5

- Yucca plant (Yucca glauca) and moth (Tegeticulla yuccasella).6

- Male and female moths come together on yucca plants to mate and form a cocoon that adult moths emerge out of in the spring.6

- Once emerged, when female moths are ready to lay eggs, she first collects pollen from a yucca flower, packs the pollen into a ball, and flies to another yucca flower.6

- At the second yucca flower, she moves to the bottom and opens small holes in the ovary then lays her eggs inside.6

- After she lays her eggs, she places a little bit of pollen from her pollen ball and packs it into slight indentations on the style.5

- She may lay more eggs in the same ovary or fly to another flower and do the same process over again. Either way, upon departure, she signals with a pheromone that tells other moths that they are not the first to lay eggs in that flower and the moth will either lay fewer eggs or go to another flower to lay eggs.5

- This communication is vital because if there are too many eggs in one flower, the plant will kill off the flower. The larvae feed on yucca seeds when they hatch and if there are more larvae than seeds, the larva will starve.5

- When the larvae finish eating seeds, they burrow out of the fruit typically during rainfall and burrow into the ground to make cocoons and awaits the next spring when the process starts again.6

Literature Cited

- Ollerton, Jeff, et. al., A global test of the pollination syndrome hypothesis. Annals of Botany, Oxford Academic, Volume 103, Issue 9, Pages 1471-1480, June 2009.

- Askham, Beth. Moth predicted to exist by Darwin and Wallace becomes a new species. Natural History Museum.Science News. September 30, 2021.

- Kiester, A. Ross et. al., Models of coevolution and speciation in plants and their pollinators. The American Naturalist, Volume 124, Number 2, Pages 220-243, August 1984.

- Hossaert-McKey, Marine and Bronstein, Judith L. Self-pollination and its costs in a monoecious fig (ficus aurea, Moraceae) in a highly seasonal subtropical environment. American Journal of Botany, Volume 88, Issue 4, pages 685-692, April 1, 2001.

- Pellmyr Olle and Huth, Chad J. Evolutionary stability of mutualism between yuccas and yucca moths. Nature. November 17, 1994

- Helzer, Chris. The Yucca and its Moth. Wildlife, Cool Green Science. March 21, 2013.

- Kritsky, Gene. Darwin’s Madagascan Hawk Moth Prediction. American Entomologist, Volume 37, Issue 4, Winter 1991, Pages 206-210, October 1, 1991.

- All Drawings were produced using Procreate.